From Isolation to Vocation

Introduction

Introduction

Our last issue of TB and Cultural Competency: Notes from the Field followed Jigna Rao's journey from a devastating diagnosis of pelvic TB to inspiring advocacy for TB care and other health issues. Jigna became an advocate partly in response to the solitary nature of her experience with TB and the resulting need to actively develop her own support network to manage her illness and its repercussions. In this issue we focus on the story of Raquel Orduño, whose on-going TB advocacy began with a group of people who came together to document and portray their experiences with TB along the United States (U.S.)-Mexico border.

A Solitary Experience

Raquel del Consuelo Orduño grew up on both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border in a bicultural, bi-national family. Although TB incidence along the border is higher than the national average in either Mexico or the U.S., she heard little about TB from family members or healthcare providers as a child and then as a teacher in El Paso, Texas. In her mid-thirties, after three years of misdiagnoses with other pulmonary infections, respiratory infections and asthma, Raquel learned she had pulmonary TB. Her physical health began to improve once she started treatment, but it seemed all other aspects of her life were thrown into jeopardy by the

diagnosis.

Children were central to Raquel's professional life as a teacher and as an aunt of five nieces and a nephew. After her diagnosis she was separated from her family, staying in a room apart from the rest of the household and wearing a surgical mask. Her home isolation dragged into a second month and then a third as her medical team waited for her cultured sputum specimens to convert to negative results for TB bacilli.

After her diagnosis, the health department initiated a contact investigation, which found several colleagues and family members had been exposed to TB. Her three year-oldniece Connie was subsequently diagnosed with TB. Witnessing the impact of TB disease on Connie was more painful to Raquel than her own illness. The normally joyful little girl became fearful and reluctant to engage with others when they went to doctor's visits or when the public health workers came to provide them with directly observed therapy (DOT). Raquel was tormented by the sight of her beloved niece in tears over medications and diagnostic procedures. Raquel's physical and mental distress in isolation was compounded by the loss of familial and professional connections and deep feelings of guilt about the people who were exposed to TB during the years leading up to her diagnosis.

An Invitation to Participate

Raquel was still in isolation and wearing a surgical mask when she received a call from Eva M. Moya, an advocate and educator from the U.S.-Mexico Border Health Association, now the Alliance of Border Collaboratives. Eva invited Raquel to participate in a project called TB Photovoice. At the first TB Photovoice meeting Eva and her co-facilitators explained its goals: first, to document members' experience with TB; and second, to bring their story to public arenas in which they could influence policy and social norms. The group in El Paso was one of two getting started at the same time; the other was just across the border in the Mexican city of Ciudad Juárez. The project, Border Voices and Images of TB, aimed to give voice to the experience and lives of people affected by TB using photography as its foundation. The group would meet for several weekly sessions. Struggling to come to terms with her diagnosis, the contact investigation, and her prolonged isolation, Raquel said very little during the first meetings of the TB Photovoice group. However, she listened intently to the other participants, and what she experienced in the group had a profound impact on her.

For the first time Raquel saw others struggling with the same challenges she faced around TB disease and treatment. In the opening TB Photovoice sessions the group learned about the long history of TB in the area, its contemporary persistence along the border and funding and other resource limitations in TB programs. As the information accumulated, Raquel began to think of her illness as more than a personal burden. The TB Photovoice group represented diverse age 2 New Jerse y Medical School Global Tuberculosis Institute Continued from page 1 g roups, ethnicities, and social classes with a common B experience rooted in the social fabric of their ommunity. For instance, many members had been isdiagnosed before TB was identified as the cause of heir symptoms. Until they came to the group, each ssumed TB was difficult to diagnose because it was a isease of the past. Raquel and several other members ere receiving care for diabetes while they were being reated for symptoms of what was finally identified as B disease. yet none was told diabetes is a risk factor or progression from latent TB infection to TB disease, r that they might take longer to respond to TB reatment than people without diabetes. After realizing ow often TB goes unrecognized, especially among eople with diabetes, they began to look for root cause f misdiagnosis in a lack of training and systematic upport for healthcare providers in their area.

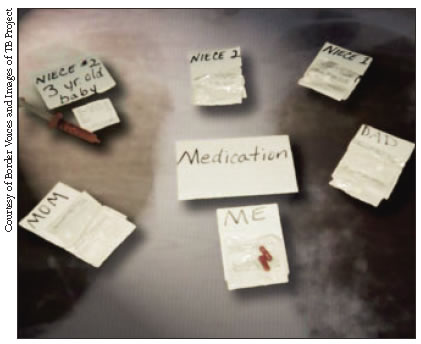

After their orientation to the problem of TB along he border, the group was trained in how to use a amera to document their TB experience. The training ncluded sessions on the ethics of taking photos in ublic and asking for people's consent before taking picture. Over the next several weeks the group took hotographs documenting the impact of TB in their ives. When they met as a group, members shared a ew pictures and talked about the setting and what otivated them to take the pictures. Taking pictures t first reminded Raquel of how difficult the months of solation were and how long the road ahead was. The pictures seemed very bleak to her: one photograph she labeled "Torture" because it showed her and Connie's medications in a big pile. Her medications were symbolic of her role as a TB patient, a role that forced her to leave her profession and remove herself from family and social activities. The image of medicines as an instrument of control that left her helpless and passive resonated in the group.

Raquel entitled this photo "The Torture", reflectinghow she initially viewed her medications. Participating in TB Photovoice helped her to see that the pills were the key to restoring her health.

Learning from Each Other

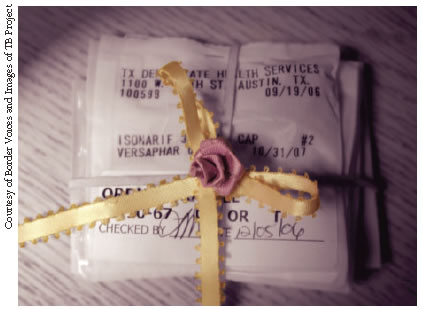

While many members responded empathetically to the picture "Torture," others reacted differently. One man shared his view of the medications as a tool to regain his health and the life that was on hold while he was sick. One of his photos depicted his hand holding TB medications, emphasizing that once the pills were in his hand he was in control of them. When she heard this interpretation of medication, Raquel felt a weight lift from her shoulders. Looking at medications from his perspective altered the way she felt about her treatment regimen and helped her to engage in treatment with her spirit as well as with her actions. Later she took a picture of her pills wrapped in a satin ribbon; a gift to restore her health. At other times, reflecting on her photos in the context of the group helped Raquel appreciate her assets. Some members went through TB in emotional as well as physical isolation, their families having withdrawn from them when they learned of the TB diagnosis. In contrast, Raquel's pictures highlighted the enduring presence of her extended family and their loving support. Once Connie adjusted to the routine of medications, her normal outgoing and cheerful disposition returned, and she came to welcome visitors from the health department. While Raquel would always view Connie's involvement as the worst part of her TB ordeal, the girl's attitude was an inspiration to her and going through treatment together ultimately deepened their bond.

An Ongoing Struggle

The common activity of showing and discussing pictures helped the TB Photovoice members coalesce as a group. Once they became comfortable sharing photos and related stories, it was a natural next step to share emotions, even tears. They became a powerful source of mutual support over the weeks they met. When one woman decided she didn't want to be publically associated with TB, it impacted the whole group, and her departure was a reminder that stigma around TB was very much a force in their experience with the disease. Some of Raquel's immediate family counseled her that relatives would stop interacting with her household if she let them know she had TB. In fact, some relatives did stop coming to Raquel's home for a while. However, TB Photovoice had inspired Raquel to respond to misunderstanding and fear with education and discussion instead of withdrawal and silence. She talked more with her family about what she was going through and learned although TB was rarely spoken of in their extended family; the disease had always been present. years before, several relatives were treated for TB and latent TB infection; an aunt had died from the disease. This information dramatically changed Raquel's perception of TB. Instead of TB being a unique affliction that set her apart from the rest of her family and society, it was an experience linking her to past generations in an ongoing struggle to access necessary health resources and education.

Raquel Orduno's photo "The Gift of Health" shows medication as a gift she gives herself. It is the counterpart to the image "Torture"

Reaching out to the Community

In addition to fostering mutual support among group members, the aim of TB Photovoice was to extend its insights and lessons into the larger society. They decided to exhibit photographs from their group and from the TB Photovoice group across the border at a local art gallery. The gallery exhibition was planned and launched with support from the University of Texas at El Paso and the local TB program. As the exhibition took shape with photographs and captions in progression along the gallery walls, the breadth of TB's impact along the border and the depth of its penetration into the lives of those affected came into sharp relief. Some TB program workers were obviously moved by the collection of photographs and expressed how much they learned about the experience of people undergoing treatment with them. Seeing that the exhibition made a difference in how TB program staff perceived people affected by TB was deeply satisfying to the group members.

"TB Cemetery" is Raquel Orduno's photo describing her wish to lay fear, stigma, shame, isolation, guilt and misdiagnosis of TB to rest.

Becoming an Advocate

For Raquel, participation in TB Photovoice led to new career paths and a passionate dedication to eliminating TB. After finishing TB treatment, she completed a Master of Social Work degree in the School of Health Sciences at the University of Texas at El Paso. In the years following her collaboration in Border Voices and Images, she spoke to local, national and global audiences about her experience with TB and the social and political contexts in which TB thrives, such as poverty, lack of awareness and inadequate funding for TB programs. Her focus gradually broadened, linking TB advocacy to efforts to strengthen access to healthcare in impoverished communities and among underserved populations, especially women and children. She currently serves as community representative to an international consortium of TB researchers, ensuring that the perspective of people directly affected by TB is incorporated into the design, conduct and dissemination of research.

A House for Reflection

As Vice-President of the TB Photovoice Board, Raquel continues her involvement in collaborative expression of the human face of TB. She also helped to launch Nuestra Casa (Our House), a travelling, three-dimensional exhibition representing the living conditions of people affected by TB in one area of Mexico. Nuestra Casa is built in the style of housing in shantytowns on the outskirts of Mexican cities. Its three small rooms are filled with furniture, clothing, cooking utensils, toys, books, decorations and other family belongings. Crowded among them are photographs, drawings, and written testimonials of how TB affected "TB Cemetery" is Raquel Orduño's photo describing her wish to lay fear, stigma, shame, isolation, guilt and misdiagnosis of TB to rest. the lives of families and individuals living in or on the edge of poverty. The setting allows visitors walking through the rooms to understand the context in which TB spreads through communities. Visitors exit the house through a walkway filled with posters and messages calling for a greater mobilization of resources and efforts to eliminate TB. On the porch, visitors write comments and messages on small pieces of cloth that are hung like clean laundry on a line in front of the house. Since it was built in 2009, Nuestra Casa has travelled to several states in Mexico and the U.S. It is now the focal point of a community-based public health initiative at the University of Texas at El Paso.

To learn more about Nuestra Casa, please visit http:// nuestracasainitiative.net/index.html and http://www. soluciontb.org/principal/nuestraCasa.php

What I Learned from Photovoice

Photovoice gave Raquel insight into many aspects of her illness and its treatment. Insights came from reflecting on her own pictures, comparing her pictures to those of others, and group discussions of images with others. Some of Raquel's insights are below.

Role Models Are All Around

When Connie was diagnosed, her illness was the most devastating aspect of my struggle with TB. She and I were always together and it felt like our bond, which was so precious to me, had inflicted the disease on her. Seeing her fear and discomfort with the treatment wounded me. But as Connie adjusted to DOT and to my being in isolation, she regained her cheerful, imaginative self. My Photovoice pictures testified to her important role in my eventual recovery – she was in so many of them. Where other members' photos often showed places they could no longer go, empty spaces in which they were absent, my pictures were filled with Connie's energy and playful inventiveness. In her eyes, my mask meant I was a doctor, so when we played she switched my role from invalid to the doctor who called the shots. Her game reminded me that much in life depends on how we interpret it. Once she was accustomed to their visits she welcomed the DOT workers with affection. Her attitude helped me to think of them as allies in my cure, rather than accomplices to my misery.

Well into my treatment I realized I was one of several relatives across the generations who had been affected by TB. It was hard to learn so late about their experiences, especially knowing personally how difficult it was. At the same time, knowing others had passed through the same trial gave me a sense of endurance and strength. It was important to me to feel I was part of a history larger than my own that ran through generations and locales in our region and was in its way as much a part of our culture as our language, food and religious traditions.

Silence Fosters Stigma

Like others in my TB Photovoice group I knew very little about TB in contemporary society before I was diagnosed, but I had the impression that the disease was largely eradicated. My diagnosis seemed like a rare throwback to an earlier period. This feeling of being an outlier contributed to the stigma I perceived around being identified as a person with TB. The silence about TB within my family and in healthcare settings was also stigmatizing and seemed to suggest my condition was too horrible to speak about. When we started to talk in TB Photovoice about our common experiences and the prevalence of TB along the border, and especially when my family started to talk about TB among us, the sense of being a throwback lifted.

Photovoice: A Medium For Global and Community-Based Advocacy

What is Photovoice?

The Photovoice methodology has been widely used for nearly 20 years as a way for people who are affected by a social issue to participate in defining the issue and developing public responses to it. It has been used to document and portray collective experiences of homelessness, environmental contamination, gender inequality, the spread of HIV and other social and health problems. Its use of photography to represent and communicate community experiences distinguishes Photovoice from other forms of community-based participatory research and mobilization for social change. Photography is a powerful medium that both documents objective facts and is a creative, artistic expression of subjective experience. Photogenic images are easily shared, even across cultural and linguistic divides, and can be readily produced by people of all ages and levels of education. 1,2

How Photovoice Works

- Photovoice group facilitators are trained to implement the methodology

- Once a topic for Photovoice has been defined, faciliatators and stakeholders recruit community memebers directly impacted by the topic to participate

- More discussion among participants and facilitators mayh refine the definition of the problem to be addressed

- Participants are trained in the use of cameras and the ethics of public photography

- Participants individually photograph elements in their communities and homes that capture what the topic means to them and how it affects them

- At Photovoice group meetings, participants share their images with each otehr, explain the context of the pictures, and reflect on why they chose to capture their images

- Based on their discussion of images, participants develop key themes that contextualize and define how they experience the issue

- These themes are the foundation of the "voice" that Photovoice projects

- The group develops and implements a plan to bring its photographs and descriptions of the images into public setting swhere the work can impact policy and public action on the topic addressed

The Photovoice is an on-going effort to integrate the knowledge and experience of people directly affected by TB into debates and policy developmentabout how best to respond to the global challenges of TB. It is led by a groupd of healthcare professionals researchers, and activists whose lives were fundamentally affected by the experience of TB.

Since 2006, TB Photovoice projects in the United States, Thailand, Brazil, the U.S.-Mexico Border, 11 states in Mexico, South Africa, and the Philippines, have brought the experiences of people who are treated for TB into local, national and international policy discussions, and helped to put a human face on the complex, persistent challenges of TB around the world.

In addional to supporting photography-based narrations of the lives and experiences of people affected by TB, TB Photovoice creates forum for its participants to join international, multidisciplanry discussions about the global challenges of TB. As a result of such participation, the group issued a Call To Action to Eliminate TB.

To learn more about TB Photovoice and to see some photographs from the project, please visit http://www.tbphotovoice.org/index.php and http://www.soluciontb.org

Advocacy Benefits People Living with TB

Advocacy in healthcare is in part a natural extension of mutual support among people grappling with the effects of a disease. Some benefits that patients gain from participating in support groups can also result from participation in advocacy especially those related to empowerment: integration of treatment into other aspects of social and family life, engagement with providers, improved understanding of disease and its treatment and greater awareness of and access to services.

Advocacy Benefits TB Programs

Advocacy is the act of championing or arguing for a cause. Effective advocacy combines scientific rigor with passion and eloquence. It connects data from diverse sources with appeals to act on the information to produce change. Whether it is provided by an individual or through a group, advocacy is a valuable resource for local, national, and global TB programs. TB advocates can increase public awareness of issues related to TB control and elimination; push for policy changes; identify and mobilize important stakeholders; and provide support for TB patients and their families. Advocates can be especially powerful allies for TB programs when they address their own communities about issues related to TB control and prevention.

The Global Plan to Stop TB 2011-2015 includes empowering people with TB and communities with partnership as a key component of the strategy to dramatically lower the global incidence of TB. Patient empowerment and advocacy enhances the lives of those with TB as well as TB programs.3

What's In A Name?

"You use the term 'patient'; I prefer to say a person affected by TB. I don't like the term 'patient,' because I was way too patient for three years, waiting for someone to give me a correct diagnosis for my condition! In retrospect I wish I had taken a more assertive role in looking for a full explanation of my symptoms. We are people first and always, not patients."—Raquel Orduño

In a recent issue of the International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease several TB specialists from across the globe published a call for TB programs and policy leaders such as the Stop TB Partnership to adopt language that supports the humanity, autonomy and dignity of people receiving TB care.4 Diverse groups of activists, patients and providers have pointed to terms that characterize people affected with TB in detrimental and stigmatizing ways:

- Labeling people with possible TB "suspects" positions them on par with subjects of criminal investigation;

- Describing people who are lost to follow up as "defaulters" presumes they willfully rejected fully accessible care and treatment and deflects attention from possible root causes such as hard-to-reach clinics, high costs for treatment, poorly trained staff, or other system-level barriers to care; and

- By naming their services TB "control," programs suggest people suffering with TB lack control and require a hierarchical, authoritarian response.

TB providers can build their awareness of how language and official terms affects the people they care for simply by listening for alternate vocabulary and asking others how they would like to be referred to and the terms they would prefer to use.

The Power of Social Support

Photovoice serves as a kind of uspport group for people in shared circumstances. For Raquel, TB Photovoice was a valuable source of information about TB. It helped her recognize many others had similar experiences. This helped minimize the emotional toll of stigma and helped Raquel develop attitudes and perspectives that supported her treatment. Education, normalizing the illness experience and building positive attitudes are recognized as important aspects of social support, associated with improved health outcomes across many conditions.5 While people undergoing medical care gain support from family, friends, co-workers, and healthcare providers,5,8 the support of others sharing similar experiences can be uniquely powerful.

Facilitate by a professional or by group members themselve, support groups can be effective sources of support for people undergoing treatment for health conditions.8 Groups may be structured around educational topics or building skills like medication adherence, or they may follow an open agenda to allow for free-flowing discussions.9 However, a support group functions, facilitators should follow key steps to ensure its success:

Understand and address potential barriers to group attendance

Individuals interested in attending support groups may encounter diverse barriers, including practical limitations and fear of stigma.10 Ways to address barriers include:

- Offer transportation to group venues or reimbursement for travel expenses

- Provide refreshments

- Use a trained facilitator to lead the group

- Consider holding the group in a setting where stigma is less of a concern, such as a community center, library or school. Even in this case some potential participants may e concerned about being publically identified by other group members or facilitators

- Offer activities that group members value

- Photovoice is an example of the power of group activity to build cohesion among relative strangers. Select activities that are meaningful to group members and can be easily mastered.10

- Allow time for group identity to develop

- Expect attendance at a new group to build slowly before it takes root

- Be prepared for changes. Even when it is well established, a group "personality" will change over time as members come and go and reveal more of themselves in the group.

Manage division within a group

Although shared experience often brings people together, it does necessarily not erase deep differences that may exist. Community rivalries, class and ethnic differences, even subcultural divides, may create rifts in a support group that can be difficult to navigate for both participants and facilitators.

- Allow separate spaces for smaller groups

- Have carefully facilitated group discussions about divisions to allow members to overcome divisions in the group setting

To learn more about creating and findisng support groups, visit the following websites:

References

1. Wang CC. Photovoice: a participatory action research strategy applied to women's health. Journal of women's health/the official publication of the Society for the Advancement of Women's Health Research. 1999;8(2):185-92. Epub 1999/04/01. PubMed PMID: 10100132

2. Wang CC, Pies CA. Family, maternal, and child health through photovoice. Maternal and child health journal. 2004;8(2):95-102. Epub 2004/06/17. PubMed PMID:15198177

3. The Global Plan to Stop TB 2011-2015.

4. Zachariah R, Harries AD, Srinath S, Ram S, Viney K, Singogo E, et al. Language in tuberculosis services: can we change to patient-centred terminology and stop the paradigm of blaming the patients? [Perspectives]. The International journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2012;16(6):714-7. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.11.0635.

5. Berkman LF, Social support, social networks, social cohesion and health. Social work in health care. 2000;31(2):3-14. Epub 2000/11/18. doi: 10.1300/J010v31n02_02. PubMed PMID: 11081851.

6. Alexander JA, Hearld LR, Mittler JN, Harvey J, Patient-Physician Role Relationships and Patient Activation among Individuals with Chronic Illness. Health services research. 2012;47(3 Pt 1):1201-23. Epub 2011/11/22. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2011.01354.x. Pubmed PMID: 22098418.

7. Rapkin B, Weiss E, Chhabra R, Ryniker L, Patel S, Carness J, et al. Beyond satisfaction: using the Dynamics of Care assessment to better understand patients' experiences in care. Health and quality of life outcomes. 2008;6;20. Epub 2008/03/12. doi: 10/1186/1477-7525-6-20. PubMed PMID: 18331632; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2323370.

8. Hogan BE, Linden W, Najarian B. Social support interventions: do they work? Clinical psychology review. 2002;22(3):383-442. Epub 2007/01/05. PubMed PMID: 17201192.

9. Miller JE, Effective support groups: how to plan, design, facilitate, and enjoy them. Fort Wayne, Ind.: Willowgreen Pub.: 1998.64pp.

10. Visser MJ, Mundell JP. Establishing support groups for HIV-infected women: using experiences to develop guidng principles for project implementation. SAHARA J: hournal of Social Aspects of HIV/AIDS Research Alliance/SAHARA, Human Sciences Research Council. 2008;5(2):65-73. Epub 2008/08/19. PubMed PMID: 18709209.

Let Us Highlight your Case

Have you, or a colleague faced a TB case that was challenging due to your patient's cultural beliefs or practices being dissimilar from your own? Have you experienced success in a case because you changed your typical approach based on something you learned about the patient's culture? If so, we'd love to highlight your case in an upcoming issue. Don't worry about producing a polished piece – we do most of the work! Please contact Jennifer at campbejk@umdnj.edu if you have some ideas.